The Body of the Snake;

fighting to save Snake River salmon

A wild steelhead swims upstream inside a fish ladder at Lower Granite Dam.

The warm, slack water below Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River creates a stagnant environment that can be lethal to salmon. In 2015, nearly all the river’s sockeye run perished due to heat, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

These populations are at high risk of extinction. A dam employee counts salmon passing through the fish ladder.

Nico Higheagle (Nez Perce), who works at the Kooskia National Fish Hatchery, shows some of the injuries a spring chinook sustained while returning from the ocean

In August 2021, the Nez Perce fisheries department collected salmon below Lower Granite Dam and transported them to their cooler natal river, the Clearwater, to protect them from the dangerous dam passage and the hot reservoir. Here, workers trap and sort out salmon that are ready to spawn.

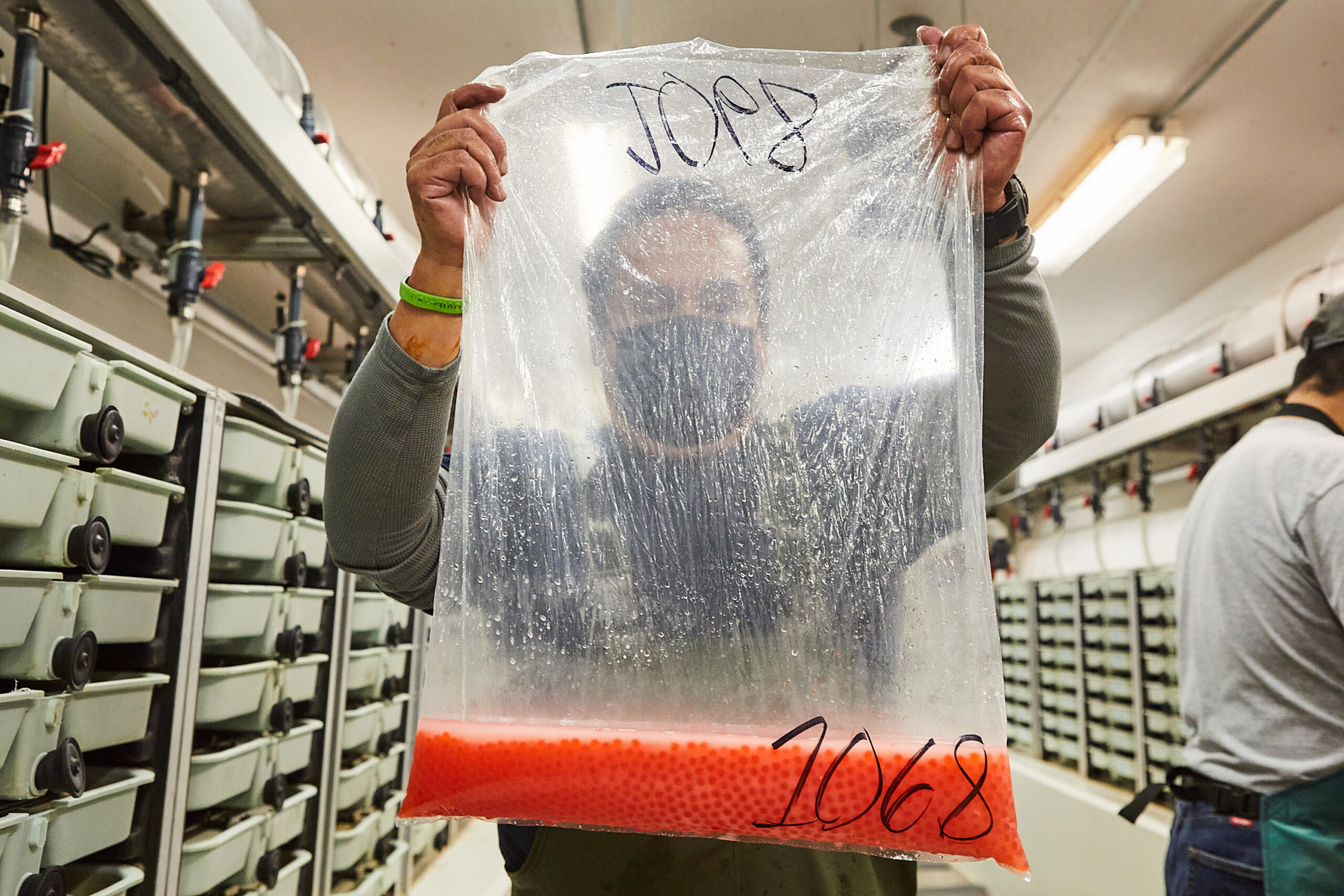

Nez Perce tribal members collect salmon sperm and eggs. Later that day they will be mixed together by hand and then placed in incubation trays. In nature, after salmon lay eggs and deposit sperm in their nests in river bottoms, they protect the nest for several days and then they die. Nutrients from their carcasses provide nutrients for their babies. In the hatchery, the carcasses of salmon that have provided sperm and egg for hatchery fertilization are placed back into the river.

Dworshak Hatchery sits on the banks of the Clearwater River, a tributary of the Snake. Without hatcheries, most salmon species would already be extinct. Although the Nez Perce supports dam removal, they have hatchery programs in place to prop up the salmon population until then.

A Nez Perce fisheries employee holds up a bag of salmon sperm and eggs at the tribal hatchery

Fertilized eggs spend several months in trays at the hatchery before hatching.

Juvenile Chinook salmon swim in an acclimation tank at Dworshak Hatchery. When they are large enough, they are released into the river.

Mark Drobish, hatchery manager for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at the Dworshak Hatchery, tosses a live steelhead into the back of a truck filled with water. In the mid-20th century, the federal government ignored biologists’ warnings that wild salmon would be decimated by dam construction.

A young Nez Perce man cleans a Coho Salmon he caught in Lapwai Creek a tributary of the Snake River.

Salmon eggs are also edible, and tribe members have different recipes.

A tribe member packages salmon fillets. Diabetes and obesity plague the tribe, which has been forced to move away from its tradition salmon diet. The tribal council is trying to combat this with its salmon buy-back program. Tribe members bring in their catch and receive $25 per salmon; it's filleted and frozen. Needy tribal members can get up to three frozen salmon fillets per week for free.

Nico Higheagle scans a returning Spring Chinook salmon in July, 2022. The hatchery fish sustain the Nez Perce’s ability to fish. Anyone who catches a wild salmon must throw is back. They are too rare.

Historically, 50% of the Nez Perce Diet consisted of salmon, which they fished ten months of the year. Today there are so few salmon in the river, catches are limited. The 3,500 tribal members are lucky if the catch limit allows them each one salmon per year.

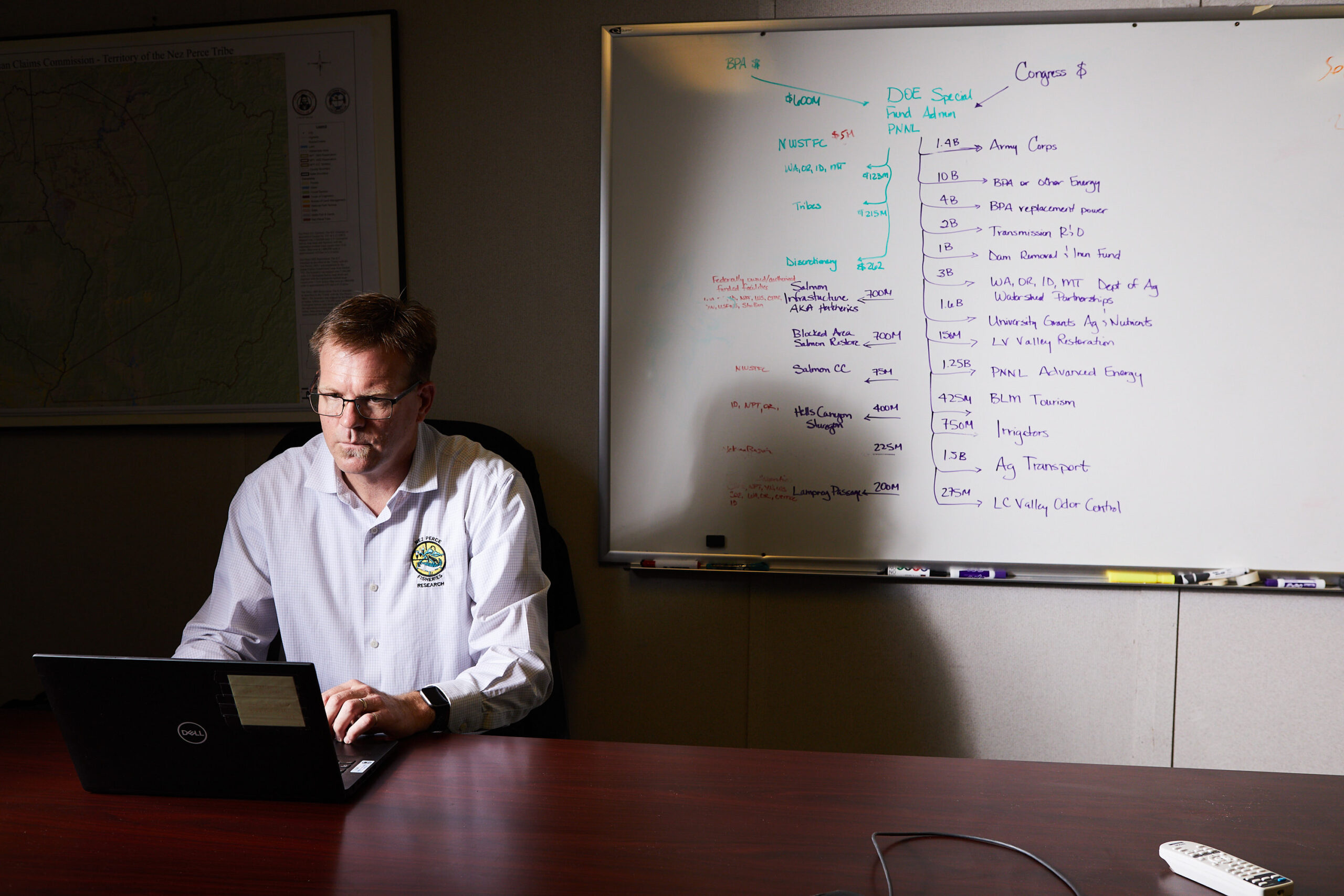

Jay Hesse: a biologist for the Nez Perce Fisheries department in front of a whiteboard outlining dollar costs of dam removal. Recent analysis shows that 42% of the Snake River salmon population is on the brink of extinction. By 2025, 77% of the population is expected to reach that threshold. He worries the action on dam removal won't be taken soon enough.

Brandon Bisbee fishes with a dip net on Rapid River. The government has spent over $17 billion on hatcheries for the Snake and Columbia rivers, yet salmon continue to decline. Biologists, conservationists, federal fisheries managers and tribal leaders believe more is needed to save the fish, including dam removal

Lee Whiteplume (Nez Perce) stands on a platform on the Clearwater River, a tributary of the Snake, where he uses a hoop net to catch salmon. In 1855, the Nez Perce tribe was forced to give up 7.5 million acres of their homeland in what is now Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. In exchange, the United States government guaranteed them perpetual fishing rights in the places they had traditionally fished.

Bill Wheeler (Nez Perce). By 1980, salmon stocks were so low that state authorities banned fishing. The Nez Perce protested by fishing as usual, but were arrested for exercising their treaty rights. Wheeler remembers friends thrown in jail in the morning who returned to fish the same afternoon after being released on bail.

The "Second Nez Perce War" ended peacefully in 1982. Illegal fishing charges were dismissed when Idaho District Judge George Reinhardt ruled that the tribe's treaties gave its members the right to fish in their ancestral streams regardless of the state's actions. That year, the tribe started its first hatchery.

The Nez Perce petroglyph on the rocks on the banks of the Snake River are about 2000 years old and depict people and animals. In Nez Perce mythology, the salmon gave its voice to the Nez Perce who promised to protect them. The Nez Perce, who have inhabited the land for many generations, were some of the first to notice the damage that dams were doing to the salmon and other species like lamprey.

Keyen Singer, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, carries on a maternal legacy of conserving salmon and preserving culture: "I feel my role is to be here for my family who can no longer fight. A lot of them worked to secure the spots and right to fish, but now we’re losing the fish." As CTUIR Youth Leadership Council’s cultural ambassador, Singer is spreading awareness to her peers about the significance of salmon. Their petition asking the public to support their call to action has generated more than 25,000 signatures to date.

Ten years ago, this housing development in Kennewick, Washington, was covered by wheat fields. Before that, it was arid desert. In the distance, green alfalfa fields are irrigated with water from the Snake River. As the region’s population increases, its demand for water and energy is exploding

Lewiston is the furthest inland port in the western United States, thanks to Snake-Columbia River dams. Water from the Snake transformed this naturally arid region into a place wheat, and even cherries, are grown. Damned rivers mean a predictable water flow, guaranteeing farmers a reliable water source for irrigation; it also allows farmers to transport wheat cheaply on barges, an impossibility on a wild river. Many farmers oppose dam removal for these reasons.

The remains of a cannery at the mouth of the Columbia River. In the 19th and early twentieth centuries, salmon returned to the Columbia-Snake River Basin by the millions. They were so plentiful, they were sometimes left to rot on canneries floors. Before dams, overfishing decimated the population.

Dr. Deborah Giles works as a conservation biologist on San Juan Island with her dog, Iba. The dog sniffs out whale feces in the ocean and guides her to samples. "Whale feces is an amazing product. We can get information about genetics, pregnancy and even what river the prey came from." says Giles.

The Southern Resident orca population consists of only 75 animals and is on the endangered species list along with Snake River salmon. These whales require 400 pounds of food per day. They eat only Chinook salmon. In the past, a Snake River salmon weighed 100 pounds, and the whale only needed to catch 4 per day. Today, salmon weigh an average of 12.5 pounds. The whales have to search farther and longer and suffer as a result.

"The whales' bodies show us what we've done wrong on this planet, help us see the folly of our behavior, and give us a chance to change it." Says Giles

Published in:

-greenpeace magazin (Germany)

The Body of the Snake

In 1855, the Nez Perce tribe was forced to give up 7.5 million acres of their homeland in what is now Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. In exchange, the United States government granted them perpetual fishing rights in the places they had traditionally fished.

But in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, logging, overfishing, and habitat destruction decimated the once-thriving salmon population. Today, salmon are being driven to the brink of extinction by a network of government-funded dams/ hydroelectric dams built between 1934 and 1984, as well as warming temperatures and changing ocean chemistry.

The latest analysis shows that 42% of the Snake River salmon population is on the brink of extinction. By 2025, 77% of the population is projected to reach that threshold.

According to the Nez Perce creation myth, salmon in these waters used to be able to speak, but they gave their voice to humans. "Now," says Shannon Wheeler, the tribe's vice chairwoman, "we have to speak for the fish."

Growing awareness of the damage is leading to consideration of removing the dams to help fish populations recover.

In the fall of 2021, U.S. Congressman Mike Simpson (R. Idaho), the National Congress of American Indians, sport fishermen and river conservationists submitted a proposal to the Biden administration to remove four dams on the Snake River to help salmon make the 1600-mile journey from Idaho's glacial rivers to the Pacific Ocean and back.

The proposal has been met with fierce opposition from inland farmers, who use the river's locks to cheaply transport grain. Businesses that rely on hydropower and Republican congressmen also opposed the idea.

But the Nez Perce say their way of life and the salmon they support will be sold down the river if the effort fails. Once a balanced ecosystem centered on salmon that fed the Nez Perce people, the river is now one of America's most endangered river. Dave Johnson, Nez Perce tribal member and biologist, said the fight is "a civil rights issue."

In October 2021, I began documenting the river, its dams, and the Nez Perce's attempts to save endangered salmon species through hatcheries and habitat restoration. I also recorded interviews with biologists, politicians, and tribal leaders.

In July 2022, I returned to Idaho, Washington, and Oregon to document the forces threatening salmon survival in the Snake River. I spoke with a cherry farmer who depends on the Snake's regular water supply; she fears that her farm and those of other farmers would disappear if the dams were removed.

I interviewed a young Nez Perce activist who, along with other young Native Americans, has been advocating for salmon nationwide and pressuring the Biden administration to work to remove the dams.

And finally, I spoke with a whale biologist who reported how declining salmon stocks are threatening the entire ecosystem and wipe out the Southern Resident killer whales that depend on Chinook salmon.

Of the southern killer whales that feed primarily on salmon, there are only 75 left, and they are in danger of starvation.

Whether the dams will come down and salmon habitat will be restored, or whether inaction will lead to the extinction of salmon in the Snake River remains to be seen.

My photos document this precarious moment and all that is in danger of being lost.

-Hayley Austin